On Thursday, 2/12/2026, we (Alex LaFollette and Erin LaFollette) became the first people to create and also document Leonardo da Vinci’s invention of the Lifebuoy Ring by using only Renaissance era materials and techniques.

We would like to give a huge thanks to Furioso Vineyards for sponsoring this experimental archeology adventure! If you are 21 and over, make sure to check them out at https://furiosovineyards.com/

Scroll to the bottom of the page for images that document our work.

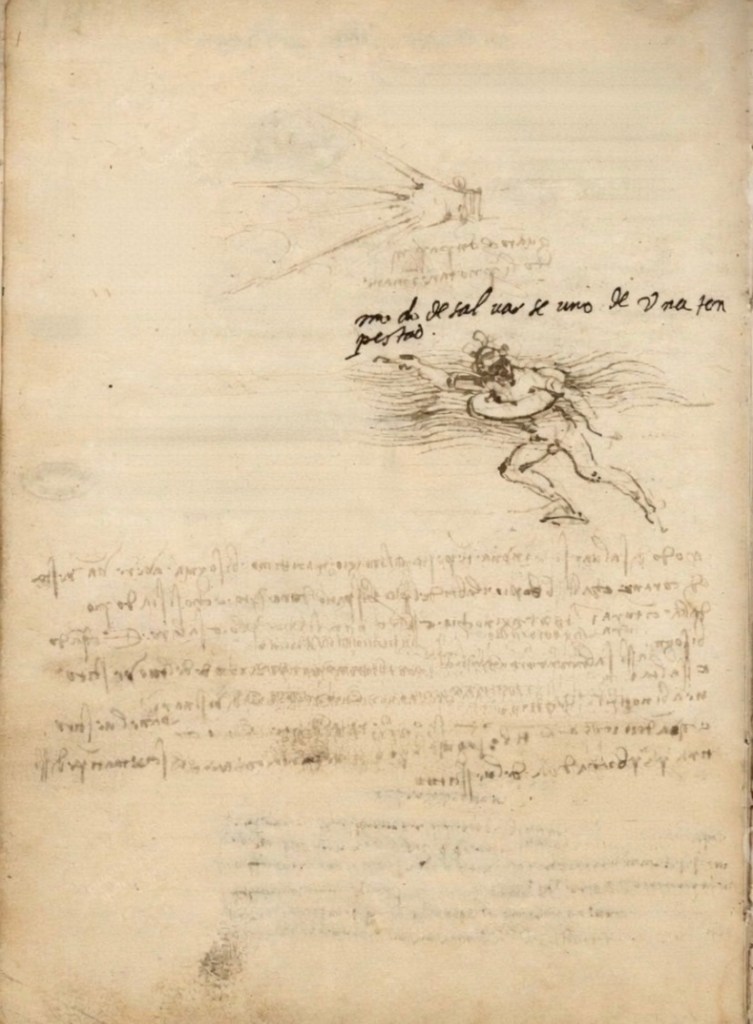

Leonardo da Vinci invented the concept for the Lifebuoy Ring (aka Life Preserver or Safety Wheel) sometime between 1485 and 1500. He drew a small sketch of a man in water wearing a Lifebuoy Ring around his torso. Da Vinci did not write any instructions on how to craft it or the specific materials to be used.

The image can be located in Paris Manuscript B, f. 81v.

While Leonardo da Vinci never created this himself, versions of it has been created in modern times, usually for museum exhibitions. However, no one has ever created da Vinci’s Lifebuoy ring using only Renaissance era materials and techniques. Museum exhibitions that have their own lifebuoy recreation follow the design closely, but utilize modern methods: chemically treated wood, modern tools (including electric ones), modern internal fasteners for stability, and other modern interventions.

There is no documented case of anyone authentically creating Leonardo da Vinci’s Lifebuoy ring until now.

We built da Vinci’s lifebuoy ring using only materials and techniques available in the Renaissance era, while strictly following components referenced in his notebooks.

Leonardo’s vision worked beautifully.

This makes us the first people to document the authentic construction of da Vinci’s lifebuoy ring using only period-accurate materials, methods, and techniques. No machines, electricity, or modern material, techniques, or interventions were used.

MATERIAL USED:

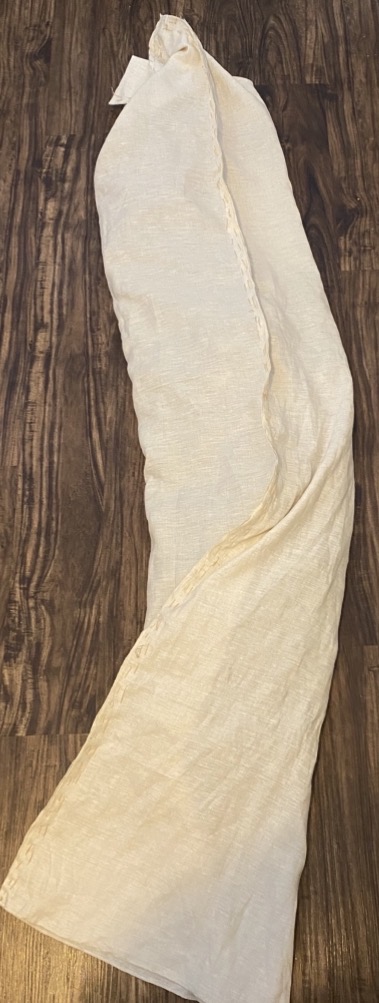

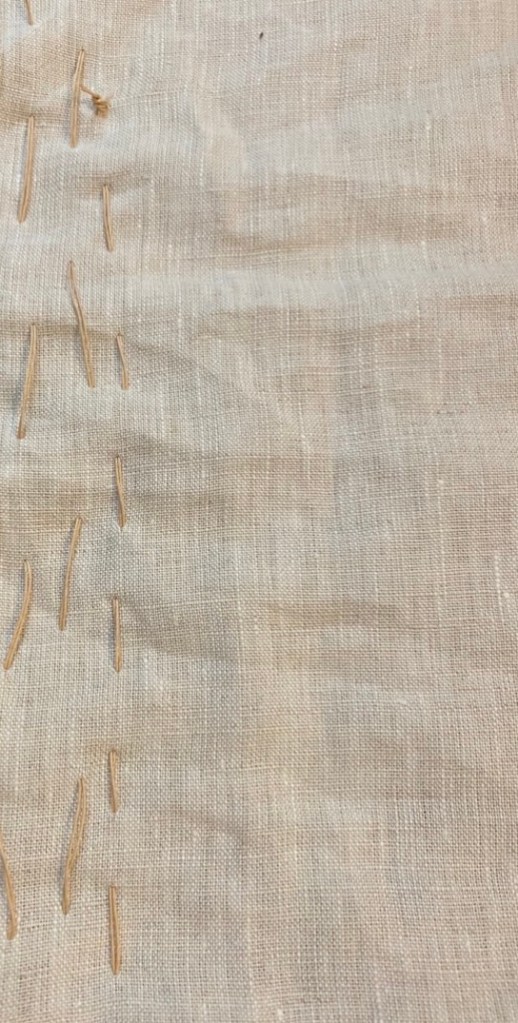

-100% Pure Linen (2.5 yards x 1 yard)

-Pure Linen Thread

-Natural Wine Corks with zero additives (~700 corks)

-Steel Needle

-Beeswax for waterproofing

NOTE:

-Everything was hand sewn with a basic steel sewing needle, which is what would have been used in the Renaissance.

-Absolutely zero modern materials or techniques were used to create this Lifebuoy Ring. No modern chemicals or additives are in, or involved in, our construction.

-We decided to use 100% natural wine corks because this is still completely the same type of cork used in this era. Cork has been used as a floatation device long before da Vinci’s sketch, but the concept of using large blocks of cork did not occur until at least the middle part of the 16th century. To keep it period-accurate, wine corks closely resembled the size of cork that Leonardo would have used for the build.

THE WHO:

Alex and Erin LaFollette

THE WHAT:

Constructing Leonardo da Vinci’s Lifebuoy Ring with only period-accurate materials, methods, and resources. This has never been done before.

THE WHERE:

Our home. No workshop, no computers, no modern measuring tools, no shortcuts at all.

THE WHEN:

Officially completed 2/12/2026 (ongoing updates for experimentation purposes)

THE WHY:

We created Leonardo da Vinci’s Lifebuoy Ring not just to be first in a technical sense, but more importantly in a meaningful sense. We wanted to show what it would have actually looked and felt like if it was made by human hands in the 15th century with the stuff da Vinci had access to. It had never been done before, and we wanted to show what the actual concept would have looked like.

THE HOW:

Folding the linen, inserting corks, and hand-sewing seams.

THE MATH:

Core Equation for Net Buoyancy per Cork

The net buoyant force (extra upward lift) from one fully submerged cork is the weight of water displaced minus the cork’s own weight:

Net lift per cork = (ρ_water – ρ_cork) × V_cork × g

Since we’re working in weight units (grams or pounds) and g (gravity) cancels out when comparing weights, we simplify to mass terms (as buoyancy is often expressed this way in practical calcs):

Net lift per cork (in grams) = (1 – 0.24) × 18 = 0.76 × 18 ≈ 13.7 grams

(Or in pounds: ≈ 0.030 lb per cork, since 1 lb ≈ 453.6 g.)

This means each cork provides about 13.7 g (or 0.03 lb) of extra lift beyond floating itself.

Main Equation for Number of Corks

N = B_required / lift_per_cork

Where:

• N = number of corks needed (round up for safety).

• B_required = required extra buoyancy in grams (or consistent units).

• lift_per_cork = net lift per cork ≈ 13.7 g.

N = B_required / [(ρ_water – ρ_cork) × V_cork]

Or, plugging in numbers (using grams for precision):

N = B_required (grams) / (0.76 × 18)

N = B_required (grams) / 13.68 (≈ 13.7 for rounding)

Examples

1. For minimal support (~7 lb extra buoyancy, lower end for very buoyant people in calm water):

7 lb ≈ 3175 g

N ≈ 3175 / 13.7 ≈ 232 corks

2. For conservative/reliable support (~10 lb):

10 lb ≈ 4536 g

N ≈ 4536 / 13.7 ≈ 331 corks

3. For safer margin (~12 lb, as in your ~500 suggestion range):

12 lb ≈ 5443 g

N ≈ 5443 / 13.7 ≈ 397 corks

So, 300–400 corks is a solid calculated range for most adults to keep the head comfortably above water.

We used approximately 700 corks to ensure total safety and flotation success.

HISTORY OF DA VINCI REPLICAS:

Over the years there has been incredible recreations of da Vinci’s inventions, including his lifebuoy. However, they have always been constructed with modern materials, methods, and resources.

Comparison to Earlier Recreations: The 1995 Niccolai Teknoart / Artisans of Florence Lifebuoy Ring

In 1995, the Niccolai firm (now closely associated with Artisans of Florence and the Museum of Leonardo da Vinci in Florence, Italy) launched a groundbreaking project to recreate over 60 of Leonardo da Vinci’s inventions as interactive, functional models. This included a version of his lifebuoy ring (or life preserver), featured in their “Hydraulics and Naval Marvels”.

Their models are described as being hand-crafted by skilled Florentine artisans, largely using materials available in the Renaissance. Each piece is paired with a facsimile codex page, and follows da Vinci’s original sketches.

These recreations are impressive educational tools that bring da Vinci’s ideas to life for millions to experience. However, as interactive displays designed for repeated public handling, travel, and long-term durability, they incorporate practical modern conveniences that diverge from strict Renaissance-only methods:

• Modern aids in the process: Official descriptions note the use of “modern day technology” for interpretation, exact scaling, proportion calculations, and structural feasibility which often involve computer-aided design (CAD) tools to refine models before physical construction.

• Durability enhancements: To withstand thousands of interactions and global tours without rapid wear, the models require subtle contemporary reinforcements, such as modern preservatives or sealants on materials, reinforced stitching, and secure fasteners. These elements were not available in the 15th century but are essential for museum reliability.

• No explicit purist claim: While they stress “faithful replicas” and “materials applied in the Renaissance period,” the emphasis is on educational authenticity and interactivity rather than absolute historical reenactment (e.g., no electricity in the machines themselves, but workshop realities in the 1990s–present would include contemporary tools for preparation and assembly).

In contrast to our 2026 reconstruction (which used only 100% period-accurate materials: pure linen, linen thread, natural wine corks, beeswax, and a basic steel needle, and strictly manual techniques with no modern interventions) the Niccolai/Artisans approach prioritizes robust, long-lasting exhibits over uncompromising purity. Their lifebuoy ring remains one of the most prominent and earliest documented physical recreations, but it represents more of a hybrid of Renaissance inspiration and modern practicality to effectively serve museum audiences.

Their project pioneered the revival of da Vinci’s mechanical legacy for public education, and we greatly respect their craftsmanship and impact. Our goal was to push one step further: an experimental archaeology build with zero post-Renaissance compromises.

Comparison to Earlier Recreations: Roberto Guatelli’s Leonardo da Vinci Models (1950s–1980s)

Roberto Guatelli (1904–1993), an Italian engineer and master model maker, was a pioneer in bringing Leonardo da Vinci’s inventions to life. Starting in the 1940s, he and his small team (including his wife and assistants like stepson Joseph Mirabella) built dozens of functional, working models from da Vinci’s codex sketches. Sponsored by IBM and exhibited widely in the U.S. and Europe, these interactive displays introduced millions to Leonardo’s mechanical genius.

The models were beautifully crafted and operational, covering flying machines and military tanks, as well as a controversial “calculating device” from the Codex Madrid. They served as powerful educational tools.

However, unlike a pure Renaissance-era recreation, Guatelli’s builds were products of 20th-century industrial methods:

• Modern workshop environment: Made in professional studios in Italy and New York using electric power tools, precision lathes, milling machines, and contemporary measuring instruments. None of which was available in the 15th century.

• Materials and finishes: Inspired by period woods, metals, ropes, and fabrics, but enhanced with modern varnishes, synthetic glues, machined metal parts, refined bearings, and reinforcements for reliable operation and exhibition longevity.

• Engineering approach: Guatelli applied mid-20th-century knowledge to interpret and refine sketches, often adding subtle improvements (e.g., better balance or reduced friction) while staying true to the original spirit. Contemporary accounts describe them as “modern working models.”

These were never claimed as strict historical replicas using only Renaissance tools and materials. Instead, they prioritized demonstration, durability, and spectacle which is ideal for the museum and corporate exhibitions of the 1950s–1980s.

Note on the lifebuoy ring: No documented evidence exists that Guatelli ever built da Vinci’s lifebuoy ring. His nautical focus was on items like the diver’s apparatus and double-hulled ships. Regardless, the broader point holds: his influential work relied on modern craftsmanship.

We have enormous respect for Guatelli’s legacy as a true pioneer who brought Leonardo’s ideas vividly into the modern era like no one before.

Our 2026 recreation of the lifebuoy ring takes a different path: a strict, experimental archaeology project using only hand tools, 100% Renaissance-available materials (linen, linen thread, natural cork, beeswax, basic steel needle), and zero post-15th-century interventions. It accurately demonstrates what a 15th-century Florentine artisan could actually have produced.

This makes us the first ones to create Leonardo da Vinci’s Lifebuoy Ring using only period-accurate materials and methods. No shortcuts. No modern interventions.

LIFEBUOY HISTORY:

Before da Vinci’s design, floatation safety devices were often built out of inflated animal bladder or cork. However, the cork structures were not ring shaped, which meant a person in water had to rely on throwing their arms over a more-rectangular shaped flotation device.

The Knights of Malta are credited with the first systematic use of circular, cork lifebuoys beginning in the middle part of the 16th century, This is well after Leonardo’s passing in 1519. These lifebuoys designed by the Knights of Malta were called Salvenos. The difference between da Vinci’s theoretical design and the Knights of Malta’s design is that da Vinci’s was personalized to the swimmer’s size. The Knights’ lifebuoys were large, bulky, mass-produced, and not individualized.

From there, the development of the lifebuoy went through major changes-

Alternative Invention: In 1928, Peter Markus patented the first inflatable life-preserver.

18th Century: Juan José Navarro, 1st Marquess of Victoria, introduced cork lifebuoys to the Spanish Navy around 1752.

19th Century: “Knight Spencer” invented the “Marine Spencer” in 1803, made of 800 corks.

Modernization: Lt. Thomas Kisbee invented the “Kisbee Ring,” which became standard equipment for the RNLI in 1855.

After hundreds of years of refining the lifebuoy, the very first idea and design belongs to none other than Leonardo da Vinci.

Please check back for future updates!

-Alex LaFollette and Erin LaFollette

Final Product!